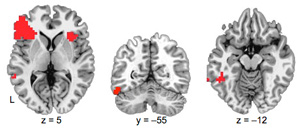

Reading presents a significant challenge for individuals who are born deaf because they cannot hear the language that is encoded by print. The factors that lead to skilled reading for deaf individuals are currently under debate and not well understood. This project uses behavioral, neurophysiological, and neuroimaging measures to identify what factors predict variations in the brain’s response when deaf adults read and recognize written words (e.g., spelling ability, phonological awareness, signing ability, reading speed).

The brain bases of reading in deaf adults

These studies are designed to examine brain functions during reading for deaf people who are bilingual in English and American Sign Language and to understand how the brain systems that support reading are shaped by deafness, e.g., by the changes in visual attention and phonological abilities that result from congenital hearing loss. We use both functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electrophysiological measures (EEG/ERP) to investigate neural systems that support reading, fingerspelling, and signing in deaf individuals. We are addressing the following questions:

- What is the neural-behavioral signature for highly skilled deaf readers?

- Does deafness impact the neural response to visually presented words?

- Can we de-couple effects of deafness from effects of low literacy on reading behavior?

- Does fingerspelling engage the Visual Word Form Area?

- How does knowledge of ASL impact word reading?

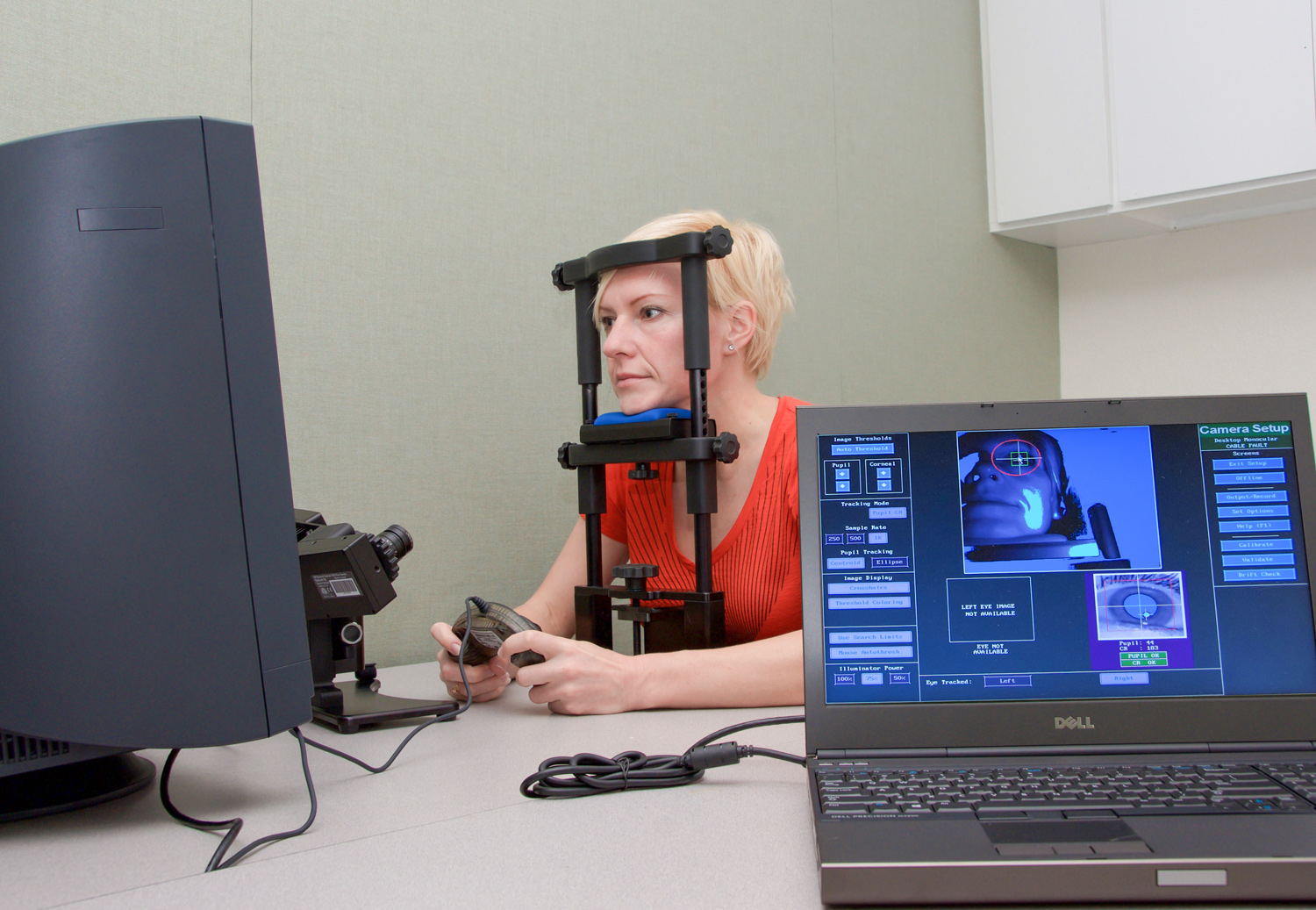

Eyetracking studies of deaf readers

Eye movements provide very good clues to how people read words and text. Our lab is now equipped with an Eyelink 1000+ (from SR-Research) eyetracking system which will allow us to determine with great precision where the eyes move when comprehending written text or when viewing sign language. Using this technology, we can ask the following questions:

- Do deaf and/or hearing signers activate ASL when they read English text?

- Do young deaf readers have a wider perceptual span (region of effective vision) during reading, relative to young hearing readers?

- Which visual and linguistic processes do skilled deaf readers use during written word processing?

- Do native signers (hearing or deaf) activate English when they process sign language?

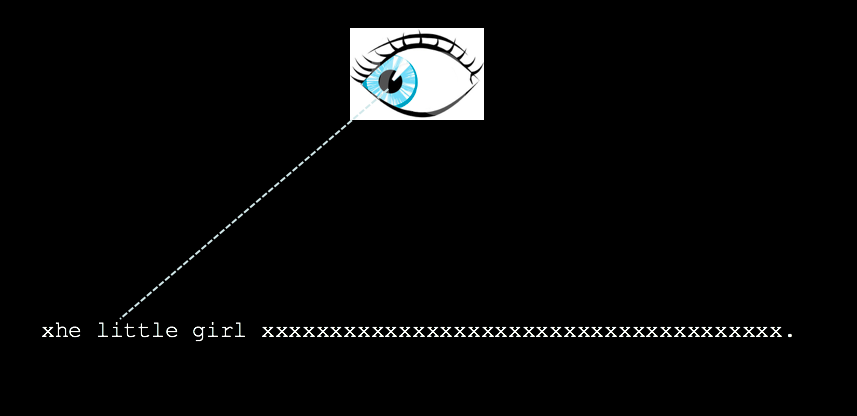

Recent work with adult and young deaf readers show that skilled deaf readers’ eye movements when they read simple sentences are very different that those of hearing readers of comparable reading skills. Deaf readers are more efficient when they read sentences compared to hearing readers with equal comprehension levels. For example, skilled deaf readers make fewer fixations in a sentence. This means that each time their eyes land on a word (called a “fixation”), skilled deaf readers are able to grab more information within that fixation. Skilled deaf readers also go back in the text (reread) less often than hearing readers do. This shows that even if deaf readers make fewer fixations than hearing readers do, they also do not need to go back in the text as often as their hearing counterpart to check their comprehension. In other words, they are “efficient” readers. Some of our upcoming projects will investigate why we find these unique and efficient eye movements in deaf readers.

Funding

This project is funded by the National Science Foundation Linguistic Programs (BCS 1154313) and Cognitive Neuroscience Program (BCS 1439257), and National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01 DC014246)

Recent Publications

- Sehyr, Z.S., & Emmorey, K. (2022). Contribution of lexical quality and sign language variables to reading comprehension. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 27(4), 355-372 https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enac018or email to request PDF.

- Emmorey, K., Holcomb, P.J., & Midgley, K. M. (2021). Masked ERP repetition priming in deaf and hearing readers. Brain and Language, 214. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8299519/

- Emmorey, K.,& Lee, B. (2021). The neurocognitive basis of skilled reading in prelingually and profoundly deaf adults. Language and Linguistics Compass, 15(2), e12407. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34306178/

- Emmorey, K.,& Lee, B. (2021). Teaching and Learning Guide for: The neurocognitive basis of skilled reading in prelingually and profoundly deaf adults. Language and Linguistics Compass, 15(2), e12407. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12410 or email to request PDF.

- Emmorey, K. (2020). The neurobiology of reading differs for deaf and hearing adults. In M. Marschark and H. Knoors (Eds). Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies in Learning and Cognition, pp. 347–359, Oxford University Press. email to request PDF

- Meade, G., Grainger, J., Midgley, K.J., Holcomb, P..J., & Emmorey, K. (2020). An ERP investigation of orthographic precision in deaf and hearing readers. Neuropsychologia. PMCID: PMC pending https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107542

- Meade, G., Grainger, J., Midgley, K.J., Holcomb, P.J., & Emmorey, K. (2019). ERP effects of masked orthographic neighbour priming in deaf readers. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. PMCID: PMC6781870 https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2019.1614201

- Sehyr, Z.S., Midgley, K. J., Holcomb, P.J., Emmorey, K., Plaut, D. C., & Behrmann, M. (2020). Unique N170 asymmetries to visual words and faces reflect experience-specific adaptation in adult deaf ASL signers. Neuropsychologia, 141, 107414. PMCID: PMC7192317 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107414

- Glezer, L. S., Weisberg, J., Farnady, C. O., McCullough, S., Midgley, K.J., Holcomb, P.J., & Emmorey, K. (2018). Orthographic and phonological selectivity across the reading system in deaf skilled readers. Neuropsychologia, 117, 500-512.

- Meade, G., Grainger, J., Midgley, K., Emmorey, K., & Holcomb, P. (2018). From sublexical facilitation to lexical competition: ERP effects of masked priming. Brain Research, 1685, 29-41.

Recent Presentations

- Camilliere, S., Midgley, K., Emmorey, K., & Holcomb, P. (2022). Masked morphological priming effects in deaf readers: An ERP study. Poster presented at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society Meeting, April, San Francisco, CA. (pdf)

- Emmorey, K.(2022). The neurobiology of skilled reading in deaf adults. Scientists in Training Series, Rochester Institute of Technology, April, Virtual talk.

- Saunders, E., Holcomb, P., Midgley, K., & Emmorey, K. (2022). Assessing the strength of the morpho-orthographic segmentation route for deaf readers using event-related potentials. Poster presented at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society Meeting, April, San Francisco, CA. (pdf)

- Lee, B., Martinez, P., Midgley, K.J., Holcomb, P.J., & Emmorey, K. (2021). Sensitivity to orthotactic and phonological constraints on word recognition: An ERP study with deaf and hearing readers. Poster presented at the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading, July, Virtual meeting.

- Emmorey, K. (2019). The neurobiology of reading in deaf and hearing adults. Distinguished Language Scientists inaugural lecture. University of California, Irvine, December, Irvine, California.

- Emmorey, K. (2019). The neurobiological foundation of skilled reading in deaf adults. Keynote presentation at Teaching Deaf Learners conference, November, Haarlem, The Netherlands.

- Emmorey, K. (2019). What’s the latest research on sign language, fingerspelling, and reading in deaf adults? Invited presentation to the Horace Mann School for the Deaf, October, Boston, MA.

- Emmorey, K. (2019). The plasticity of the reading circuit. Keynote speaker at the 5th International Conference on Cognitive Hearing Science for Communication, June, Linköping, Sweden.

- Lee, B., Mirault, J., Bélanger, N., & Emmorey, K. (2019). No pronounceability effects during sentence reading by deaf and hearing readers. Poster presented at the meeting of Sign Language Linguistics Society (TISLR13). September, Hamburg, Germany. (pdf)

- Massa, N., Emmorey, K., Midgley, K.J., & Holcomb, P.J. (2019). Tracking the time-course of visual word recognition using different types of word-like stimuli. Poster presented at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, March, San Francisco. (pdf)